The Ocean Responds to a Warming Planet

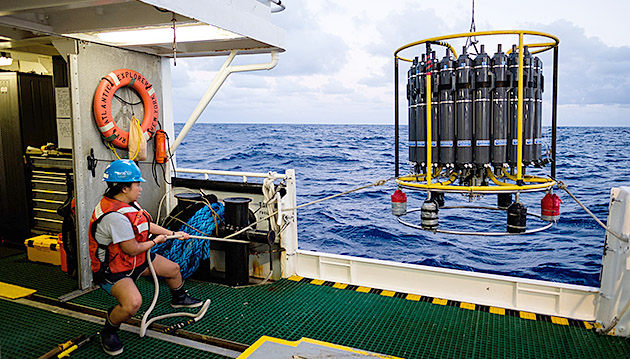

New research using data collected from two of the world’s longest-running open-ocean time-series, Hydrostation ‘S’ and the Bermuda Atlantic Time-series Study (BATS), has revealed that climate change is impacting the structure of the ocean’s water masses. A marine technician hauls in the CTD (for conductivity, temperature and depth) rosette aboard the research vessel Atlantic Explorer on a recent BATS research cruise in the Sargasso Sea. The CTD rosette collects water samples and physical oceanographic measurements from discrete depths, allowing scientists to understand how ocean properties change throughout the water column.

We are familiar with how climate change is impacting the ocean’s biology, from bleaching events that cause coral die-offs to algae blooms that choke coastal marine ecosystems, but it is becoming clear that a warming planet is also impacting the physics of ocean circulation.

A team of scientists from the University of British Columbia, the Bermuda Institute of Ocean Sciences (BIOS), the French Institute for Ocean Science at the University of Brest, and the University of Southampton recently published the results of an analysis of North Atlantic Ocean water masses in the journal Nature Climate Change.

“The oceans play a vital role in buffering the Earth from climate change by absorbing carbon dioxide and heat at the surface and transporting it in the deep ocean, where it is trapped for long periods,” said Sam Stevens, doctoral candidate at the University of British Columbia and lead author on the study. “Studying changes in the structure of the world’s oceans can provide us with vital insight into this process and how the ocean is responding to climate change.”

One particular layer in the North Atlantic Ocean, a water mass called the North Atlantic Subtropical Mode Water (or STMW), is very efficient at drawing carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere. It represents around 20% of the entire carbon dioxide uptake in the mid-latitude North Atlantic and is an important reservoir of nutrients for phytoplankton—the base of the marine food chain—at the surface of the ocean.

Using data from two of the world’s longest-running open-ocean research programs—the Bermuda Atlantic Time-series Study (BATS) Program and Hydrostation ‘S’—the team found that as much as 93% of STMW has been lost in the past decade. This loss is coupled with a significant warming of the STMW (0.5 to 0.71 degrees Celsius or 0.9 to 1.3 degrees Fahrenheit), culminating in the weakest, warmest STMW layer ever recorded.

“Although some STMW loss is expected due to the prevailing atmospheric conditions of the past decade, these conditions do not explain the magnitude of loss that we have recorded,” said Professor Nick Bates, BIOS senior scientist and principal investigator of the BATS Program. “We find that the loss is correlated with different climate change indicators, such as increased surface ocean heat content, suggesting that ocean warming may have played a role in the reduced STMW formation of the past decade.”

These findings outline a worrying relationship where ocean warming is restricting STMW formation and changing the anatomy of the North Atlantic, making it a less efficient sink for heat and carbon dioxide.

“This is a good example of how human activities are impacting natural cycles in the ocean,” said Stevens, who was previously a BATS research technician from 2014 through 2017 before beginning his doctoral work, which leverages the work he did with BATS/BIOS.

For read-only access to the full article, please visit https://rdcu.be/b3bMu